A concerto for a “trombone god”—finally, Ferdinand David’s Concertino op. 4 in Henle Urtext

Dominik Rahmer

Monday, January 31, 2022

The following is by Dominik Rahmer and was first published on the Henle blog in a slightly longer form. It is reprinted here with kind permission.

The trombone is an instrument with a venerable though also chequered history. After its first great heyday in the Renaissance and early Baroque, it long led a niche existence in the late 17th and 18th centuries. We owe to Beethoven its “reintegration” into the symphony orchestra, where it has since become indispensable (see this blog post for the 2020 Beethoven year). As a veritable solo instrument, the trombone really came into its own only in the 20th century – its diverse timbres and playing techniques were prized above all in jazz.

Image, above: Ferdinand David (1810–1873). Lithograph by J. G. Weinhold, Leipzig, 1846

The classical-romantic solo repertoire for trombone being, on the other hand, unfortunately small. One of the very few bright spots is Ferdinand David’s Concertino in E-flat major op. 4 for trombone and orchestra. This enchanting concert piece, composed in Leipzig in 1837 in the best “Mendelssohnian” style, is today one of the trombone compositions most frequently played worldwide, having become an essential standard work for auditions and competitions.

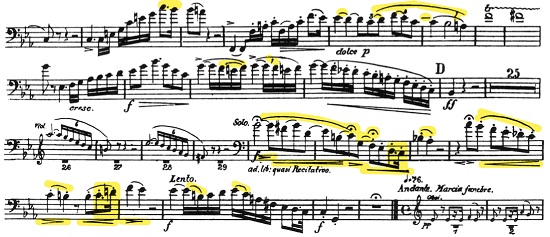

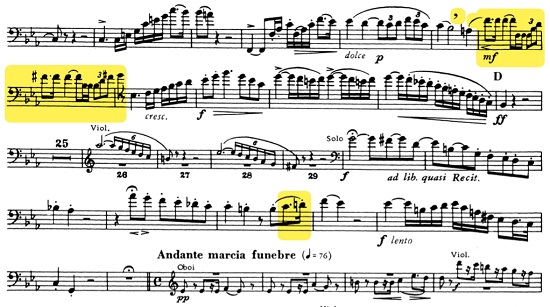

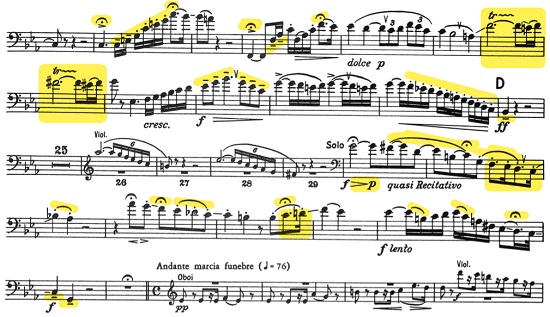

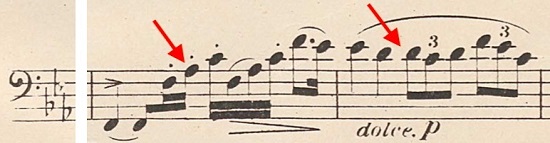

As is often the case, alas, this work’s popularity stands in stark contrast to the quality and reliability of its editions available to date. We are not aware of any modern edition where the solo part has not been “adjusted” to a greater or lesser extent by the respective editor, with supplementary details of articulation and dynamics, expression markings, changes to rhythm and pitches or even entire tone passages, everything, mind you, without identifying any as independent editorial additions. Here is a small impression of such, using the example of the last measures before the opening of the slow movement – also showing for comparison the original version of the first edition published in 1838, as authorised by the composer Ferdinand David. The most striking differences are marked in yellow:

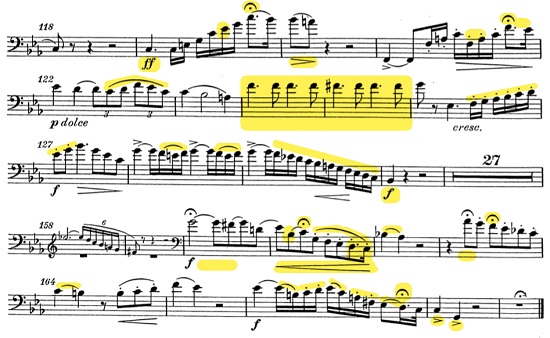

Kistner first edition, 1838, mm. 118 to the end of the first movement.

J.H. Zimmermann edition, edited by Robert Müller.

IMC edition, edited by William Gibson.

A.E. Fischer/A. Benjamin edition, edited by Fritz Grube.

Fr. Hofmeister edition, editor unknown.

G. Henle Verlag has now published a new edition with the goal of recovering the David Urtext. The editor of this critical edition is Sebastian Krause, solo trombonist of the Leipzig MDR Symphony, conservatory teacher and specialist on the history of the trombone, especially in Central Germany. Not only does Krause have decades of practical and artistic experience with the David concertino, but he also made a fundamental contribution to researching its history, in particular, with the biography of Carl Traugott Queisser (1800–1846), its first interpreter, purported to have commissioned the work.

Queisser was solo violist at the Leipzig Gewandhaus orchestra, though simultaneously also a trombone virtuoso of international standing. He then enjoyed such a great reputation in Germany and beyond that he was ranked in concert announcements on an equal footing with such artists as Franz Liszt or Ignaz Moscheles. Robert Schumann even described Queisser as a “trombone god” in an article on Leipzig’s orchestral life…! (Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, 6 December 1836, p. 185)

The Leipzig-style trombone model, such as Queisser presumably played: Wide-bore tenor-bass trombone by Christian Friedrich Sattler, 1841. Museum für Musikinstrumente der Universität Leipzig. (License: Creative Commons BY-NC-SA)

Queisser was a close acquaintance of the Gewandhaus orchestra’s concertmaster – none other than Ferdinand David, at the time one of Germany’s most famous violin virtuosos (for whom Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy composed his violin concerto). David was also active as a composer and wrote the trombone concertino, so to speak, as a tailor-made piece of music for his friend (for further details on the history of its genesis, see the preface by Sebastian Krause).

As the concertino’s autograph score has unfortunately been lost, the main source for the new edition has been the first edition of 1838 mentioned above, published in Leipzig by Carl Friedrich Kistner. It is basically a reliable source, undoubtedly reflecting David’s intentions, though the solo part has some engraving errors and inaccuracies needing correction.

Original bell section of a tenor trombone by C. F. Sattler, ca. 1840s. Private owner, Sebastian Krause

Here, a fortunate circumstance came up: in 1838 Ferdinand David produced an arrangement of the trombone concertino for cello and piano, certainly with a view to making the work accessible to a wider circle of musicians. Kistner also published this arrangement of David’s in 1838. The editor and Henle were able to locate not only an exemplar of the very rare edition, but also even its autograph! The manuscript, presently preserved in the library of Northwestern University at Evanston, Illinois, has, to the best of our knowledge, not yet been evaluated by scholars.

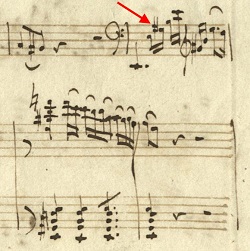

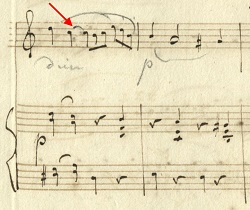

The solo part of the cello version does, of course, differ from the original in many small details, owing to its arrangement as idiomatic for a string instrument: different positioning of slurs, sometimes different broken chords and figurations, use of double stops, and much more. David furthermore transposed the piece down a semitone, to the key of D major that is better suited for the cello. This arrangement, however, often provides helpful indications and confirms engraving errors in the original trombone version. Here is an example:

In measure 121 there is no accidental in front of the a flat (which doesn’t really fit the harmony in the orchestral accompaniment), and in the following measure the repetition of the d flat1 seems strange, musically:

The cello version confirms the assumption that a natural and a tie should be added here:

Further inadvertent errors in the first edition can occasionally be found in the articulation markings. To this end, the editor Krause makes some careful supplementary suggestions, always clearly identified within brackets in the edition. For example: in comparing measures 315–317 with the analogous measures in the exposition (mm. 111–113), some details in the recapitulation, such as the crescendo hairpin and three accents, are probably only inadvertently missing in the first edition, so these were added in brackets in the new edition:

The goal of Henle’s Urtext edition is to offer musicians a secure music text as the basis for the most authentic possible interpretations intended by the composer. “Back to the source” is the slogan and the RISM database is an indispensable resource for this.

All images courtesy of the author.

Share Tweet EmailCategory: New publications