Conserving creativity—the case of Beethoven’s ‘Kafka’ sketch miscellany

Zoë Miller and Chris Scobie

Thursday, April 28, 2022

The following originally appeared on the British Library’s Music blog (© British Library Board, Creative Commons Attribution Licence).

In this blog post we look at a recent conservation project involving an important Beethoven manuscript known as the ‘Kafka’ sketch miscellany (Add MS 29801).

How did the manuscript come to be in the British Library?

The manuscript’s name comes from its previous owner, Johann Nepomuk Kafka (1819-1886), an Austrian pianist, composer and manuscript collector.

The British Museum bought it, together with a manuscript of Beethoven’s cadenza for the last movement of Mozart’s Piano Concerto in D minor and some scores by Franz Schubert and Gioachino Rossini, in 1875 for a total of £323.

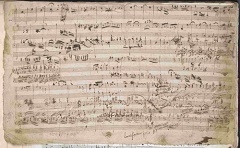

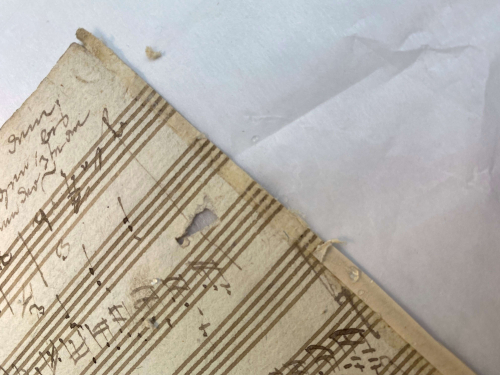

Image, above: A page from the ‘Kafka’ sketch miscellany, Add MS 29801, f. 88r

What is contained in the volume?

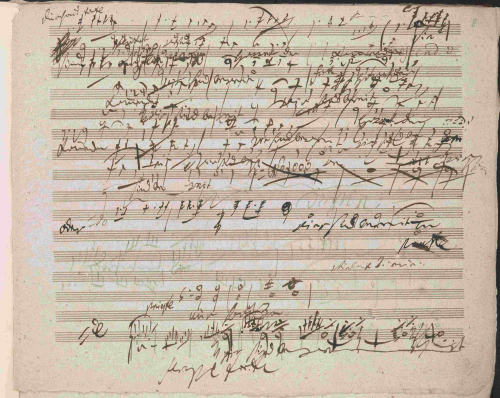

Although the ‘Kafka’ volume is sometimes referred to as a sketchbook, that is only really true of the first 37 folios, which would have originally formed a bound entity in their own right. This section dates from about 1811 and shows the in-demand Beethoven at work on music for the play Die Ruinen von Athen (‘The Ruins of Athens’) – now most famous for its overture and ‘turkish’ march.

Sketches for Beethoven’s music for the play ‘The Ruins of Athens’, Add MS 29801, f. 8r

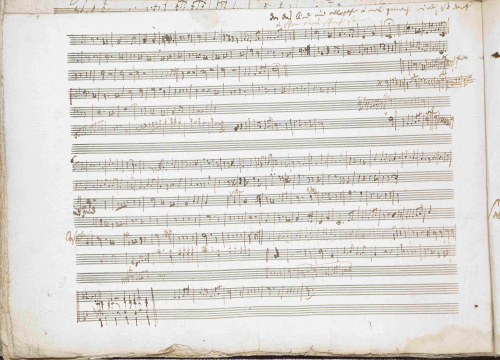

The rest of the volume (ff. 39-165) is actually something of a jumble. The earliest of these pages date from about 1781 when Beethoven was just 11 years old. There are also examples from throughout his early life, charting his formative years, his move from Bonn to Vienna in 1792, and the period following that when he was busy establishing a name for himself.

Beethoven probably kept leaves like this unbound, perhaps revisiting them at different points in his life. It seems unlikely that he kept them in any kind of consistent order, but even if he had, they are unlikely to have retained it after his death. There was a lively market for manuscripts and mementos of the composer through the 19th century, and such relics changed hands frequently – often, sadly, with the result of related pages being separated and scattered among different owners.

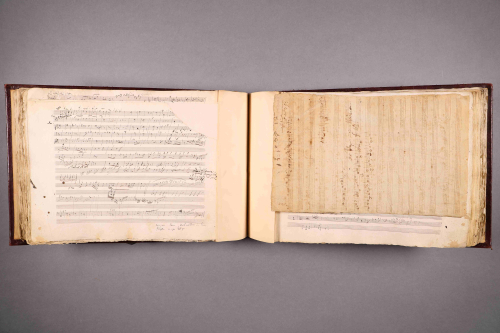

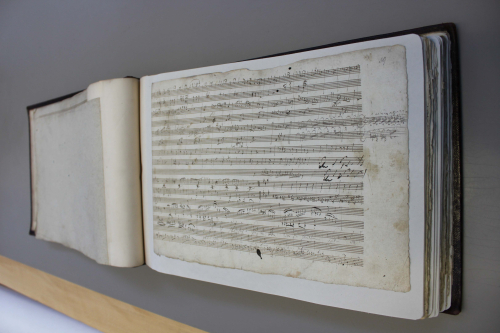

An opening of Add MS 29801, showing leaves mounted on guards. Photograph by Zoë Miller.

This particular bundle of miscellaneous leaves were brought together with the 1811 sketchbook into a composite volume at some point after Beethoven’s death, with each individual folio eventually mounted on a small stub of paper (known as a guard) and bound together.

The contents of these pages range from relatively neat drafts of complete pieces – like this movement of a sonatina for mandolin and piano – to barely legible scribbles, capturing ideas quickly in a burst of inspiration.

A folio showing Beethoven developing ideas for an uncompleted song in C major, Add MS 29801, f. 46v.

Many examples show initial musical ideas being worked over and over, developed on the page. Sometimes these ideas came to nothing, but other times they ended up as pieces we know today.

Beethoven’s creative process, and how it is reflected on paper, has been the subject of a lot of discussion over the years, but there is a useful introduction by Barry Cooper.

What was the conservation journey of the ‘Kafka’ volume?

The ‘Kafka’ volume was flagged for conservation attention in 2019 due to a number of pages displaying wear and tear along the edges. Of particular concern was the potential loss of Beethoven’s annotations at the extremities of sometimes fragile and weakening paper.

What were the challenges?

The range of different paper and ink types in the volume, as well as the jumbled nature of the contents, presented a varied situation though, and meant that careful consideration and close collaboration between curators and conservators was important. Whatever we did needed to balance a respect for the object and its history with long-term preservation needs.

The general approach to treatment was to make the volume fit for purpose but with minimal intervention. So, we took a targeted approach, retaining the structure of the object but identifying vulnerable leaves where the paper was particularly weak or worn at the edges, or where text was in danger of being gradually worn away.

Vulnerable and exposed paper at the fore-edge of the volume. Photograph by Zoë Miller.

A fragile leaf on removal from its guard, prior to repair work. Photograph by Zoë Miller.

Another factor we considered was how the volume is used, both now and in the future. It had already been digitised, and a facsimile and transcription of the contents were published in the 1970s, and these have helped reduce the number of times the volume is handled for study.

What’s next for this iconic manuscript?

As an iconic manuscript in public ownership, it is something that we want to be able to display periodically, both at the British Library and occasionally on loan to other institutions.

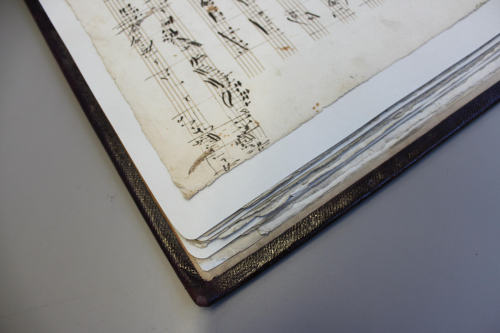

Given the disparate content there are many possibilities as to what might be chosen to be exhibited. The fact that the manuscript is bound means either displaying the whole volume or else needing to lift individual leaves from the guards. The latter is certainly possible, but not something to be undertaken regularly or repeatedly. In prioritising leaves for conservation work, we took into account the likelihood of use in future displays.

Work in progress – inside the British Library Conservation Centre. Photograph by Zoë Miller.

As well as some small paper repairs to support areas of fragile ink and small tears to the edges of some folia, the main solution was to remove the identified leaves from the original guards and hinge them onto a sheet of archival handmade paper with fine Japanese tissue.

Add MS 29801 after work to create support pages. Photograph by Zoë Miller.

Detail showing the new support pages. Photograph by Zoë Miller.

This both helps to reduce direct handling of the manuscript pages and to create a buffer between the inks, which themselves can have a deteriorating effect over time. Additionally, this treatment will help make it easier for particular folios to be removed from the volume for display without damage or disruption in a sufficiently stable condition to withstand transport and display requirements.

Finally, a custom–made drop back box was constructed to better support the volume while in storage, providing a buffer against the environment and a safe way to transport it.

This conservation work was undertaken with generous support from the Idlewild Trust and has meant that several leaves from this unique volume were on display in our exhibition Beethoven: Idealist. Innovator. Icon.

Selected pages of this volume are also featured on our Discovering Music webspace, where you can find out more about it – and images of all 162 folios are available to view up on Digitised Manuscripts.

Zoë Miller, Conservation Team Leader

Chris Scobie, Lead Curator, Music Manuscripts

All images used with permission.

Share Tweet EmailCategory: Library collections