Lute Manuscripts at Cambridge

James Luff

Monday, October 11, 2021

The following is by James Luff and originally appeared on the MusiCB3 Blog. It is reprinted here with kind permission.

I spent quite a bit of my spare time during lockdown learning to play the lute. So naturally, I was excited when I discovered that Cambridge has some extraordinary lute manuscripts in its collection. I’ll highlight a few of the star pieces, but in particular I’d like to talk about a more recent, and lesser-known addition to the library’s lute manuscripts: the so-called ‘Medici’ lute manuscript. But first, a bit about the lute in general.

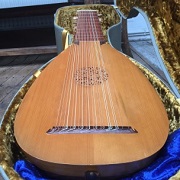

Image, left: My lute, currently on loan from the UK Lute Society – an 11-course instrument from later in the lute’s long history.

The lute was at the heart of European music-making for over 400 years. Sharing a common ancestor with the Arabic Oud, the European lute went through a series of developments in construction and tuning throughout the course of its long life. Essentially, extra strings were gradually added to the bass register, leading from the Medieval 4-course instrument—a course being a pair of strings tuned in unison or octaves—to the enormously complex 13-/14-course instruments of the high Baroque (example in the painting below).

‘Allegory of Hearing’ (c.1750) – Anna Rosina von Lisiewska (Public Domain)

With the nature of musical life eventually changing from the intimate private settings of a system of courtly patronage to large public concerts, the soft sound and increasingly complex construction of the lute didn’t find a comfortable place for itself, and the last professional lutenists alive in Europe date from around the time of Schubert.

However, it was in Elizabethan England that the lute had one of its most illustrious eras, with the period 1550–1630 being often proclaimed as the ‘golden age of English lute music’, with the leading lutenist-composers of the time including such names as Francis Cutting, John Johnson, Thomas Campion, Anthony Holborne, and, most famous of all, John Dowland.

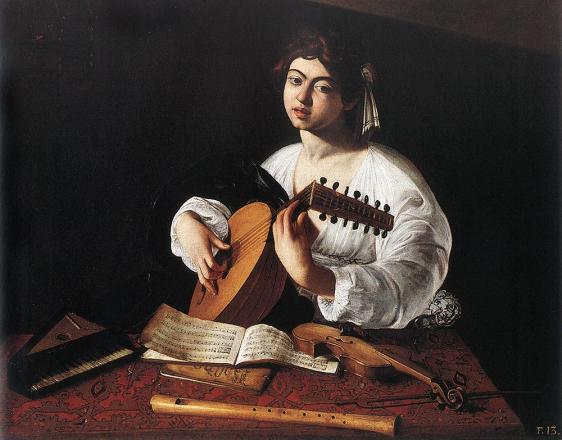

A 7-course Renaissance lute suitable for playing much of the music in the manuscripts mentioned here. ‘The Lute Player’ (c.1596) – Caravaggio (Public domain)

It is right from the heart of this period that comes the most famous of the lute manuscripts at Cambridge: the Mathew Holmes lute books. Often described as the ‘crown-jewels’ of the English renaissance lute repertoire, these four books are the most important and extensive source of English lute music to survive in the world. There are more than 600 pages crammed with over 650 separate items that preserve a complete cross-section of the repertoire in common use in England for the period 1580 to 1615, including works by all of the great English renaissance lute composers, almost all of which are for a lute of 6- or 7-courses.

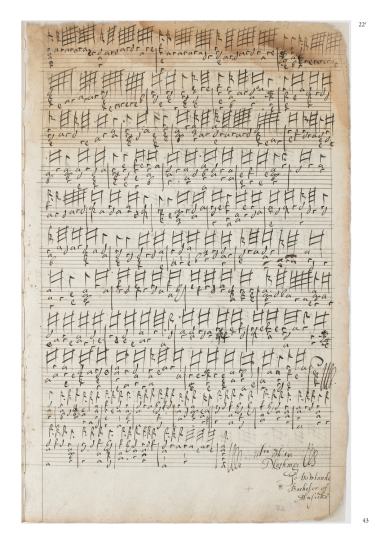

‘Mrs White’s Nothing’ by John Dowland, from the first of the Holmes lute books. CUDL image licensed under CC BY-NC 3.0

All of these extraordinary books are now freely available to view online as part of the Cambridge Digital Library, including also the Trumbull lute book – a rare example of a late 16th century personal lute book made and used by an English government official and diplomat:

Click here to view them: Cambridge Digital Library Lute Manuscripts

There are also some fascinating lute manuscripts in the Fitzwilliam museum from slightly later in this golden age (ca.1618-1640). Namely, The Cherbury Lute book (MU.MS.689) and the Lowther Lute book (MU.MS.688).

All of these manuscripts employ tablature notation. Still familiar to all modern guitar players, it’s a remarkably clear and quick-to-learn system, whereby instead of providing information about musical pitches, it simply tells you which frets to play, with the rhythm given above.

Details of Dowland’s famous ‘Lachrimae Pavan’ in the first Holmes’ lute book. CUDL image licensed under CC BY-NC 3.0

There are a few different kinds of lute tablature and the particular variety used in these lute books is the French system, which is the most widely used in lute music generally (with the other varieties being Italian and German). Here, the horizontal lines represent the strings of the lute, with the top line being the highest-pitched string and the letters indicating which frets to play: a=open, b=1st fret, c (actually written ‘r’ to avoid confusion with ‘e’)=2nd fret, d=3rd fret, e=4th fret, and so on.

The Medici Manuscript

But I’d like to pay particular attention here to the most recently-acquired, and thus lesser-known, lute manuscript in the collection: the so-called ‘Medici’ lute manuscript. This small but fascinating volume has come to Cambridge as part of the Jeanne-Marie Dolmetsch Collection (Former Dolmetsch shelfmark MS II.C.23 is now: Jeanne Marie Dolmetsch Collection MS. Add 10355).

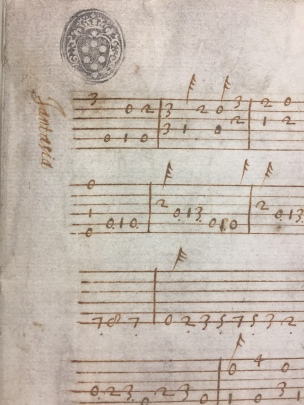

The Medici stamp on the first folio of the Dolmetsch manuscript. The piece is a ‘Fantasia’ by Francesco da Milano. ©CUL

Among the manuscripts in the Dolmetsch family library, there were three notated in lute tablature. Of these, the Medici manuscript is the oldest and contains the earliest repertoire, largely consisting of pieces from throughout the 16th century for Italian renaissance lute. The manuscript gets its name from the coat of arms stamped on the first folio. Originally conjectured to be the coat of arms of the Florentine Medici, it has been demonstrated that it is in fact identical to that of the Grand Dukes of Tuscany (1569-1737), all of whom were nevertheless members of the Medici family.

It was originally acquired by Arnold Dolmetsch at the end of the 19th century while on a tour of Italy. Reportedly, whilst paying a visit to the Marchese Torrigiani to barter over the price of an Amati violin, he noticed the manuscript on the floor. Recognising the Medici stamp, he managed to suppress his excitement enough to acquire the manuscript for a thoroughly reasonable price.

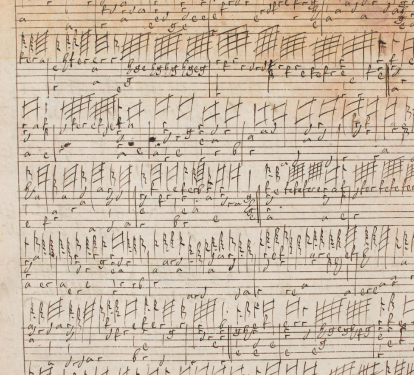

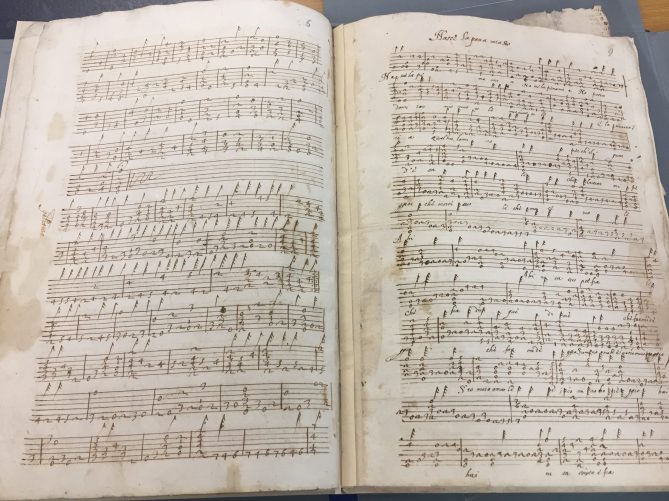

A ‘Galiarda’ followed by a setting of Alessandro Striggio’s ‘Nasce la pena mia’ with the original words written underneath. ©CUL

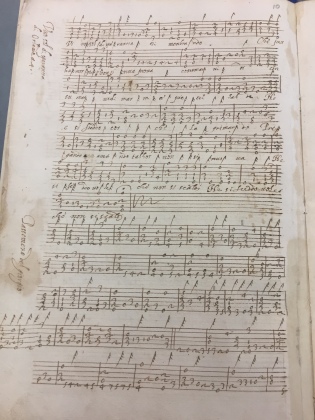

Unfortunately, the manuscript is incomplete, with only 27 folios surviving from an original of over 70. As scholar Victor Coelho says, ‘were it not for its unfortunate present condition, Haslemere [i.e. the Medici manuscript] would deserve status among the most important Italian lute manuscripts of the late 16th century.’ Nevertheless, it still contains 21 works, including examples of the main types of lute music found in this period – fantasias, recercars, intabulations of vocal music and dances, all by several of the most prominent Italian lute composers, including Francesco da Milano, Pietro Paulo Borrono, Andrea Feliciani, with the arrangements being of vocal music by leading Italian composers of the late 16th century: including Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, and Alessandro Striggio, as well as the great Flemish composer Orlande de Lassus.

An arrangement of Orlande de Lassus’ ‘Vino sol de speranze’. ©CUL

Unlike the English manuscripts in French lute tablature notation mentioned above, this manuscript employs the Italian variety. Here, instead of letters, the frets to be played are indicated using numbers, and while the six lines still represent the strings of the lute, the order is flipped, with the highest line on the page corresponding with the lowest-pitched string.

Although the Medici manuscript is a somewhat tantalising object in that its incompleteness is all that prevents it from being among the most important Italian lute manuscripts of the late 16th century, even in its current state it’s a wonderful addition to the library’s collection and contains a wealth of correspondences with music in a host of other historic sources of Italian music. And as such, it holds great potential for further scholarship regarding the details of its provenance as well as the music it contains.

Share Tweet EmailCategory: Library collections