The Library of the Landgravine Caroline Henriette von Hessen-Darmstadt (1721–1774)

Beate Sorg

Thursday, March 11, 2021

We have received the following guest post from Beate Sorg:

Goethe, who never knew her personally, called her “The Great Landgräfin.” Frederick the Great, King of Prussia, to whose entourage she belonged for a number of years, donated a marble urn for her grave in the Herrengarten in Darmstadt with the inscription “Femina sexu, ingenio vir” (a woman by sex, a man by spirit) – which might not be high praise for today’s feminists, but certainly was considered so at the time. But these apostrophes helped create legends, which often have resulted in a somewhat skewed image of her. For example, it is by no means true that this ruler assumed a large portion of governmental business for her husband, the “Soldier Landgrave,” who lived in Pirmasens and was only seldom in Darmstadt. She was also not at the center of the group known as the Sentimental Circle (Empfindsamer Kreis), which was already starting to break up by the time Caroline moved to the city in 1765, where she stayed for only nine years, until her death.

In fact, Caroline, born Countess Palatine of Zweibrücken, was a smart, educated woman, enlightened and sentimental as was typical of the time but also in the sense of a personal character description. Born on 9 March 1721 in Strasbourg, she grew up in Elsass and the Southern Palatinate as the oldest daughter of Christian III, Count Palatine of Zweibrücken. Even when she married Hereditary Prince Louis IX, Landgrave of Hesse-Darmstadt in 1741, she preferred to live at the royal residence in Bouxwiller (Elsass) and visited her spouse only when required. Unlike her husband – who exhibited Prussian correctness to the point of pettiness, was religious if not superstitious, but who was first and foremost a soldier – Caroline was interested in music and the hunt and especially in sciences and cultural pursuits. She raised her eight children with love and care, and seeking advantageous marriages for her daughters was her most important concern in her final years.

She spent hours reading nearly every day of her life. Equally important to her was corresponding with other select people about what she read. The high number of “forbidden books” is remarkable: works by Diderot, Voltaire, and other Enlightenment philosophers, atheists, and libertines whose works were burned by the imperial censors. Caroline regularly procured these writings from her Frankfurt bookseller; she defended him when he was put into jail for doing so.

Two handwritten catalogs are preserved in the University and State Library Darmstadt (D-DS) that reveal information about the library of the Great Landgräfin, even if most of the books and music listed there have been lost over the centuries. Only one of these catalogs (D-DS Hs 2267), a thick, bound book, has a significant title:

Catalogue

de la Bibliotheque

de Son Altesse Serenissime

Madame la Princeße

Heréditaire Landgrave

de Hésse Darmstadt

née Princèsse Palatine

des Deuxpontes

1763

The foreword contains a description of the six cabinets and their contents in Bouxwiller Palace. The most comprehensive section by far contains French works, followed by those in German and English. There is a lot of room for additions, though apparently thicker and somewhat darker pages were inserted later with new acquisitions until 1772. At the end are some music items, particularly operas, but those only list the items that were already in Bouxwiller.

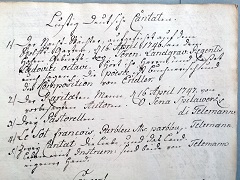

For the additions after 1763 – unfortunately we do not know when exactly – an extra catalog was started, and probably by the same writer to judge by the handwriting (D-DS Hs 2591). This thin volume, which is also called the “copper catalog” after the color of its cover, has neither title nor date nor ownership marks. It contains, arranged by genre, the music that was presumably performed in Darmstadt when Caroline resided there. Barely any works from the “old” collection of the court chapel have survived, but likely some pieces from the time of Louis VIII have, such as cantatas for his birthday. The works that make up the largest part, however, are the ones that the fashionable and always well-informed and up-to-date Landgravine had sent to her from Berlin and Paris.

Image: Excerpt from the “copper catalog,” with kind permission of the ULB Darmstadt

Share Tweet EmailCatégorie: Anniversaires