Cherubini's Best Wishes for the New Year

Balázs Mikusi

Thursday, December 19, 2024

Approaching the end of the year, we would again like to call your attention to an intriguing musical document originally conceived as a kind of new year’s wish. However, whereas the piece by Carl Eberwein we introduced to you a year ago had formulated a series of friendly greetings to a greater community, Luigi Cherubini’s Souhaits heureux pour la nouvelle année 1842 appears a personal note to a close friend, the exact implications of which may have been clear only to the two persons involved.

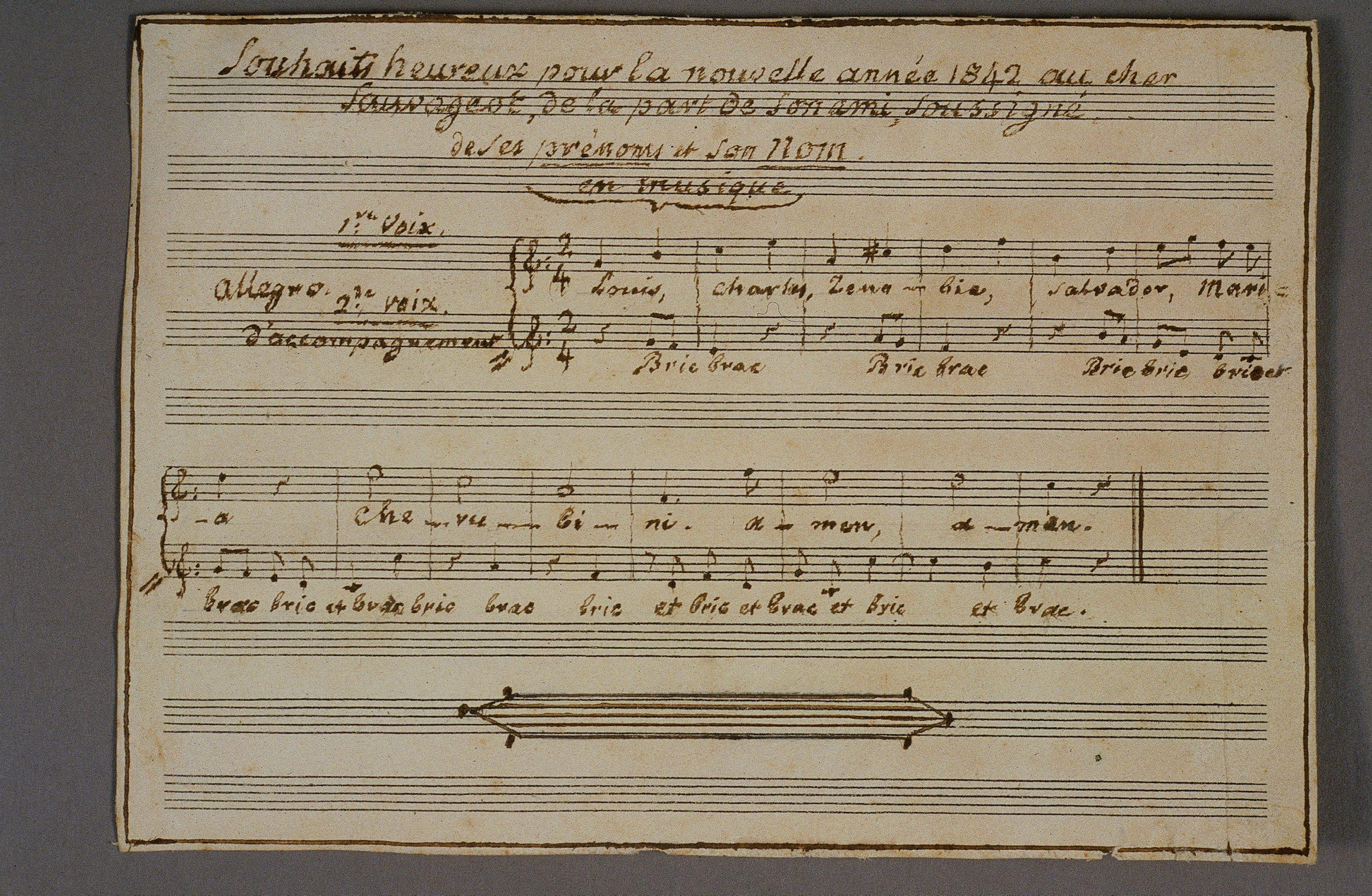

The piece happens to be one of Cherubini’s very last compositions, and in musical terms it is barely more than a playful improvisation. That said, the composer certainly gave some thought to it, as reflected by a draft of the work today kept in the Bibliothèque nationale de France that also includes some corrections (RISM Catalog | RISM Online). In fact, some of the music is barely legible in this autograph, therefore it is good luck that a clean copy of the piece – presumably the presentation copy meant for its dedicatee – has also survived in another Paris collection, namely the Musée de la musique (RISM Catalog | RISM Online):

Here one can clearly read the two voices, as well as their respective texts: “Louis, Charles, Zenobie, Salvador, Maria Cherubini. Amen, amen” on the top and a series of “bric brac” statements interspersed with “et” conjunctions at the bottom. The series of first names proves easy enough to decode: while music history textbooks as a rule refer to Cherubini as “Luigi,” his birth certificate actually included the series of five names presented here – which thus conclusively lead to the ensuing paternal name “Cherubini.” The “Amen” postlude arguably only enhances the irony of such a festive statement of the composer’s own name, and it is worth mentioning that Cherubini was so fond of this idea that a few months earlier he had already set the exact same text (with a triple repetition of “amen”) as a canon (RISM Catalog | RISM Online), in which the word “Cherubini” is in fact sung to the exact same four notes. (See the digitized version of a manuscript from F-Pn containing the same “Mon nom” – “My name” – canon but not yet cataloged for RISM.)

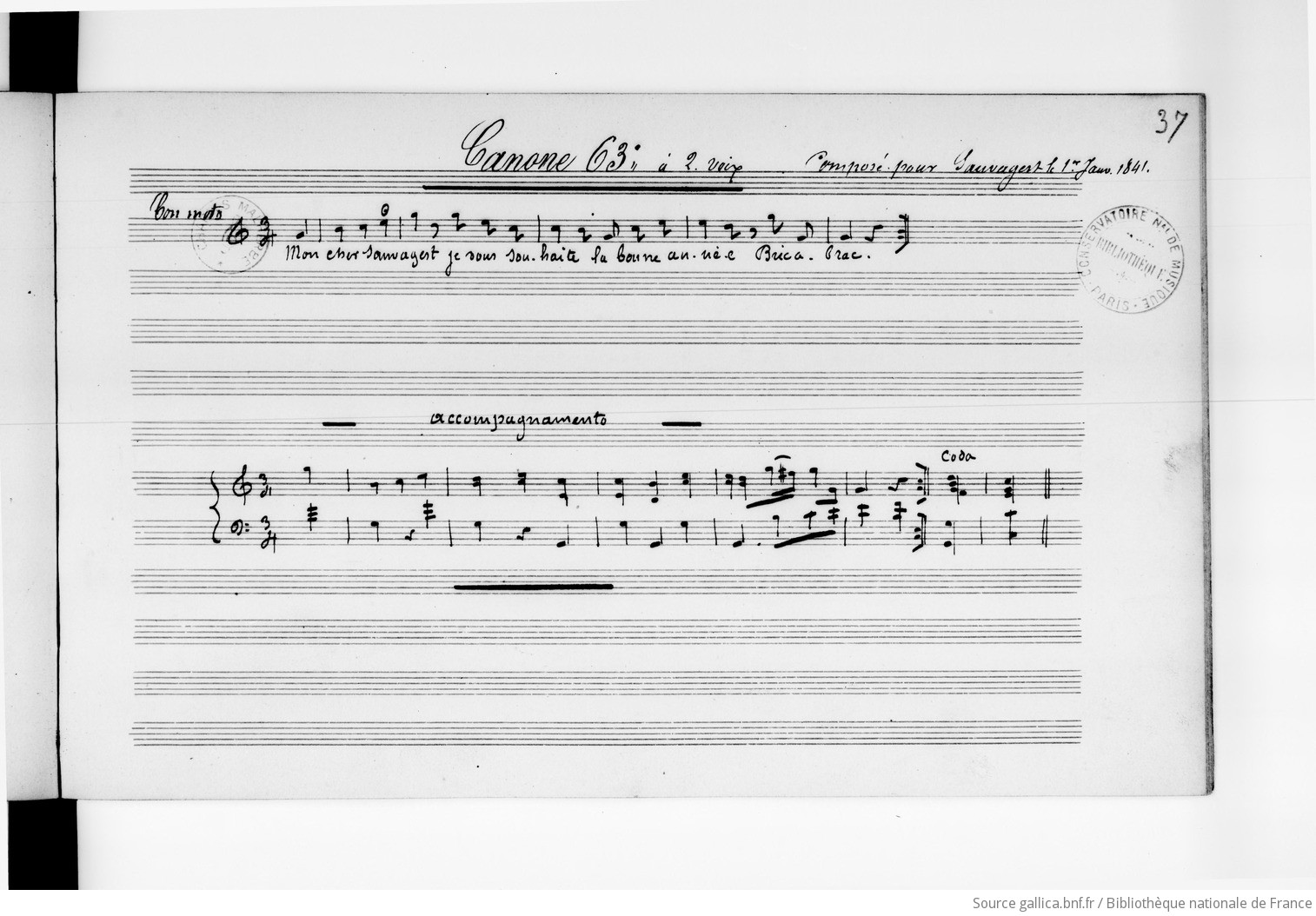

To some of our readers the text of the lower part may sound mere gibberish, but in French bric-à-brac actually refers to small decorative objects of no great value – the kind of tiny knick-knack that our grandmothers used to gather on the mantelpiece or their shelves. And, just as with the composer’s full name, the use of this expression happens to have some precedents in Cherubini’s oeuvre. Another canon, written on 15 January 1835 (cf. also RISM Catalog | RISM Online), opens with “Vive le bric-à-brac” (“Long live the bric-á-brac”) and goes on to repeat “bric” and “brac” (with a few “et” interspersed) just as Suihaits heureux does, while a third canon dated 1 January 1841 (also meant as a new year’s greeting exactly a year before Suihaits heureux) ends with the words “bric-à-brac,” used as a closing tag (a secular “amen” of sorts).

According to the entry in Cherubini’s manuscript collection of canons, this third canon (cf. also RISM Catalog | RISM Online) was “composé pour Sauvageot” – mentioning the very same name that we have encountered above in the dedication of Souhaits heureux: “au cher Sauvageot, de la part de son ami, soussigné de ses prénoms et son nom en musique.” We have seen that the latter part of this dedication provides a perfect characterization of the music that follows, in which Cherubini’s first names (“ses prénoms”) followed by his family name (“son nom”) identify him as the “undersigned.” But who is this “dear Sauvageot,” the recipient of Cherubini’s good wishes, after all? The question proves all the more intriguing, since the two must have maintained a close friendship for several years – given that the above-mentioned “Vive le bric-à-brac” canon of 1835 was also already written “pour Sauvageot.”

As it turns out, the indubitable clue to the dedicatee’s identity is precisely the expression “bric-à-brac,” which is explicitly associated with Sauvageot’s name not only in the 1835 canon and the 1842 Souhaits heureux, but also in the canonic new year’s wish of 1841 cited above, the text of which could not be more explicit: “Mon cher Sauvageot, je vous souhaite la bonne année. Bric a brac.”

For the musician’s eye and ear, the first thing to note here is that the first four notes of this piece, associated with the words “Mon cher Sauva(geot),” are in fact identical to the opening of Souhaits heureux – which thus proves essentially to be based on two quotations: that of Cherubini’s own family name (recycled in the second half from his earlier canon “Mon nom”) and that of his addressing “my dear Sauvageot” (borrowed from his new-year canon composed a year earlier). Even more intriguingly, however, the close association of the friend’s name with bric-à-brac leaves little doubt that the person in question was none other than Alexandre-Charles Sauvageot (1781–1860), a notable figure of contemporary Paris, who was accepted to the newly founded Conservatoire in 1795 (the same year that Cherubini was also employed there as an inspector), won a first prize as violinist two years later, to eventually join the orchestra of the Opéra in 1800 and remain its member for close to three decades. On the side, however, in 1810 Sauvageot also became a customs official, thus ensuring some additional income that allowed him increasingly to dedicate himself to his (as the Gazette des beaux-arts put it on 15 December 1860, when reporting about the auctioning of Sauvageot’s library) “passion pour le bric-à-brac.”

Needless to say, the expression bric-à-brac seems somewhat out of place here, if one considers the long-term results of Sauvageot’s passion: as a notable collector of artefacts especially from the Renaissance period, he effectively became one of the founding fathers of the Louvre’s Department of Decorative Arts by donating his vast collection to the museum in 1856. This celebrated donation earned Sauvageot two venerable titles (chevalier de la Légion d’honneur and conservateur honoraire des Musées du Louvre), but even a decade earlier he had been considered as such an emblematic figure of contemporary Paris that Honoré de Balzac arguably based the collector figure of his novel “Le Cousin Pons” (1847) on his personality. Nevertheless, in the final analysis, all of this sensational collector career grew out of Sauvageot’s innocent “passion for the bric-à-brac,” hence Cherubini’s associating the term with his friend’s name as a kind of epitheton ornans seems entirely justified.

In conclusion it is worth mentioning that the above-quoted journal report on the sale of Sauvageot’s library also called attention to his curious ex libris, a small etiquette Sauvageot used to put on the flyleaves of his books, featuring the motto “Dispersa coegi,” which more or less translates to “I have gathered what was scattered.” In fact, this is just what we have sought to achieve in this brief text as well, by bringing together – as pieces of a puzzle – some of the sources related to Cherubini’s peculiar new year’s wish.

Furthermore, this is also what RISM has been seeking to achieve for over 70 years now – though on a scale much larger and even more international.

Image on the top: Portrait of the old Luigi Cherubini by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1841). Photographic reproduction, Public domain.

Share Tweet EmailCategory: Events