Music and Mozart's Starling

Monday, December 3, 2018

The European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris) is wrapping up its final weeks as Bird of the Year here in Germany. The environmental organization NABU hopes to call attention to the familiar songbird and its extremely versatile vocal chords, but unfortunately the species is also facing loss of habitat and declining numbers.

The bird takes center stage in last year’s book Mozart’s Starling by naturalist Lyanda Lynn Haupt. As an American author, Haupt has a different perspective than European conservation groups, because where she lives the starling is considered an invasive species and is not necessarily appreciated as the talented mimic whose impressive displays in murmurations numbering hundreds of thousands of individuals count as one of the spectacular sights of nature. Which makes her decision to keep the pest as a pet all the more unusual. But Haupt rears a baby starling in the hopes of understanding the bird’s behavior because a famous person had the same pet around 230 years ago: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

Mozart aficionados probably already know that Mozart bought a starling in 1784 when he, so the story goes, was walking in Vienna and a familiar melody from of one of his piano concertos caught his attention. Surprisingly, the melody was coming from a starling that was for sale by a bird vendor. In his notebook, Mozart wrote out the tune from his concerto, and then the version as the bird sang it (with some errors, but we’ll forgive our feathered friend). Mozart was apparently so delighted that he promptly took the bird home with him, which lived in the household for the next three years.

To what extent this tale is true—and how the bird could have learned the tune—is one of the aspects Haupt explores in the book. She also takes a look at the music that Mozart wrote when the starling took up residence, actually beginning with the piece that started it all: the Piano Concerto no. 17 in G (KV 453), which was written for Mozart’s student, Barbara Ployer. Mozart’s own catalog of works, kept today at the British Library, begins in 1784. The time of composition, in whole or in part, for at least eight piano concertos, three symphonies, and Le nozze di Figaro can be associated with the occupancy of Mozart’s avian houseguest.

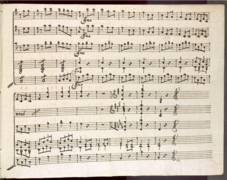

Haupt then moves to a bit of a musical conundrum. Mozart’s Ein musikalischer Spaß, KV 522, was completed in June 1787, shortly after the death—and elaborate funeral and elegy—of his beloved starling (which was, incidentally, the same year that Leopold Mozart died). Commentators through the ages, from Deutsche Grammophon to YouTube, have endeavored to hear some of the “fun” or “joke” in the title through the ways that Mozart’s melodies seem to go against the instincts of a competent composer: clumsy and awkward, it is more of a parody than a piece. But Haupt calls to our attention the work of animal behaviorists Meredith J. West and Andrew P. King, who actually think that the very aspects that are unappealing from a melodic point of view in fact bear the fingerprints of a starling. Even the end that seems to stop without notice (see image) might be heard as characteristic of the way the starling suddenly breaks off a melody.

Listen for yourself, and listen to Mozart’s other music from this period. Can you hear the twittering of a starling?

Image: Last page of Ein musikalischer Spaß in a copy held by the Czech National Library, RISM ID no. 1001011179. Available online (CC-BY).

Share Tweet EmailCategory: In the news