“One of the greatest geniuses I have ever known…”: The composer Joseph Martin Kraus

Wolfram Enßlin

Thursday, March 17, 2022

The following is by Wolfram Enßlin and originally appeared on the Carus Verlag blog. It is reprinted here with kind permission.

“What a loss is this man’s death. I have a Sinfonie by him which I will preserve in memory of one of the greatest geniuses I have ever known.”

No less than Joseph Haydn said this of Joseph Martin Kraus, one of the most interesting and exciting artistic personalities in the second half of the 18th century; because of his similar birth and death dates to Mozart, he was also described as the “Baden” or “Odenwald” Mozart. The symphony Haydn referred to was the Sinfonie in C minor VB2 142 (VB2 = 2nd impression of the Kraus Catalog of Works after Bertil van Boer 1998), in fact one of the most fascinating and thrilling symphonic compositions, stylistically still strongly linked to the ‘Sturm und Drang’ period, as was Kraus generally in his character and his artistic outlook.

Although a lot has happened to bring Joseph Martin Kraus to wider prominence over the last 30 years or so (since the 200th anniversary of his death in 1992), not least through the phenomenal recording of his symphonies by Concerto Köln, he is still something of a well-kept secret on the music scene, both in performances and in scholarship.

It stands to reason that he is constantly compared with Mozart because of their similar dates, but there almost all similarities end. Both composers left as their last composition outstanding settings of funeral music – with Mozart his incomplete Requiem in D minor KV 626, and with Kraus the funeral music for the funeral ceremonies of King Gustav III of Sweden, murdered at a masked ball at which Kraus himself was present: this comprises the Trauersinfonie in C minor VB2 148, which consists of four slow movements, the 1st movement of which begins with ear-splitting timpani strokes, and the two-part Trauerkantate VB2 42 in Swedish, versions of which now also exist in German.

Joseph Martin Kraus, born on 20 June 1756 in Miltenberg am Main in Franconia, was not a child prodigy like the slightly older Mozart. Nevertheless, his special musical talents were evident at a young age, both in singing and playing the violin; he studied at the grammar school in the Odenwald town of Buchen, where his father then worked as bailiff for the Electors of Mainz. Kraus’s parents had sent him to the Jesuit Grammar School in Mannheim, and because of this special musical talent, he was given a free place as a boarder in the Aloysianum music seminary there. There were close links between the music seminary and members of the famous Mannheim court ensemble. Thus, Kraus received lessons in composition and other subjects from Abbé Vogler and composed his first musical works at this time. Nevertheless, he did not have a clear route to a career as a professional musician. His father wanted Joseph Martin to follow in his footsteps. He therefore studied philosophy and law from 1773 in Mainz and continued his studies in Erfurt. Even though he took his studies seriously, he did not neglect his music during this period. His first surviving church music composition dates from his time in Erfurt, a Miserere in C minor VB2 4, in which Kraus revealed his varied range of musical expression with assured compositional skill. It is hard to believe that this was his first work.

Then an event occurred which was to suddenly interrupt Kraus’s studies. As a result of defamations, his father was taken to court in 1776, and because of this he was suspended from his office until the verdict was pronounced. This meant that for the time being, he could no longer finance his son’s studies. Joseph Martin Kraus returned to his family in Buchen and stayed there for a year. He was not idle during this time. On the contrary, it is thanks to these circumstances that we have many church music works which he composed for his Buchen congregation: for example, his Requiem in D minor VB2 1, a truly remarkable half-hour work, often with very short concise movements omitting some lines of text in the Sequence between the “Dies irae” and “Lacrymosa”, and the oratorio Der Tod Jesu VB2 17, for which Kraus also wrote the libretto. Kraus also had considerable literary talents, which is why he himself was sometimes undecided about whether his own future lay as a composer or a poet. At the beginning of his studies he had some pastoral poems printed which are no longer extant. He used the events surrounding his father’s trial in his drama Tolon in 1776. And in 1777 his work Etwas von und über Musik fürs Jahr 1777 was published anonymously. In this he pointedly and impulsively explained his own music aesthetic and again positioned himself here as a typical representative of ‘Sturm und Drang’. He strongly criticized, for example, the common practice in church music of composing mass settings with little relation to content, instead the tendency to set the text for splendid effect, sparing no scorn: “Before the first Kyrie a roaring Overture with trumpets and timpani was heard – the chorus joined in joyfully with great force, and nothing was spared in celebrating the piece, so the organist pulled out all the stops and with each entry he needed all ten fingers. Schmidt, Holzbauer, Brixi, Schmidt in Mainz have composed Masses: set other words to these, so they could make operettas out of them. One takes the more solidly (or whatever you call them!) arranged works by Waßmut, Pögel, Richter, the great Fux, Gaßmann – why does one need to repeat a simple Amen several hundred times? Should not music in churches be mainly for the heart? Are fugues suitable for this?”

For Kraus, the fugue, probably in its instrumental form, was of particularly high importance as long as it was used artistically. He wrote about this elsewhere: “O – thou diamond of harmonic reason – thou source of the emotions – thine is the power to enrapture the connoisseur heavenwards, and to open the lover’s eyes wide or even send him to sleep!” He then expressed his feelings about the canonic double fugue: “Thou, thou art the masterpiece of nature.”

After his one-year interruption, he resumed his legal studies and continued these in Göttingen. There he was closely involved with the Göttinger Hain-Bund literary circle. But, reinforced by the experience of his father’s two suspensions from office, he was increasingly disinclined to pursue a career as a civil servant, but instead to try becoming a musician. Here, in 1778 his career took him to Stockholm, accompanying his friend Carl Stridsberg. After three years with little work, he finally succeeded, thanks to the success of his opera Proserpin, in obtaining the position of conductor of the court orchestra. Kraus then had eleven more artistically highly-fulfilling years before he died from a long lung illness on 15 December 1792. He spent almost five of these years, from 1782 to 1786, travelling on behalf of the King to the most important musical and theatrical centers in Europe, using his experiences as a basis for reorganizing the musical life of Stockholm. In Vienna he met composers including his idol Christoph Willibald Gluck, and at Eszterháza he made the personal acquaintance of J. Haydn. In the short period before his death, Kraus was to become one of the leading musical figures of the Gustavian era.

His gravestone bears the inscription: “Here lie the earthly remains of Kraus – the divine lie in his music.” It is thanks to the Swedish diplomat Frederik Samuel Silverstolpe that a considerable portion of his musical output survives and can thus be performed at all today. In preparing a planned extensive biography of Kraus shortly after the composer’s death, Silverstolpe copied many widely-dispersed compositions and later left his collection to the University Library in Uppsala. The unique copies of no fewer than 37 compositions, including the Requiem and Der Tod Jesu, survive in Silverstolpe’s valuable music collection.

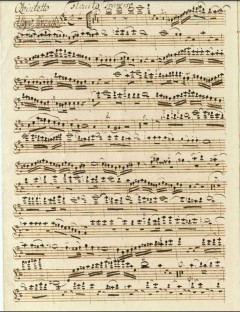

Image: Joseph Martin Kraus, Quintett für Flöte und Streicher (BoeK 184), manuscript copy in DK-Kk (mu 6404.2266), RISM ID no. 150205112.

Share Tweet EmailCatégorie: Nouveau au RISM