Music treasure lost and found

Caroline Shaw

Thursday, May 24, 2018

The following originally appeared on the Music Blog of the British Library and is © British Library Board and posted here under a Creative Commons Attribution Licence.

Music cataloguing had a rather shaky beginning in the British Library. In the Library’s early years when it was part of the British Museum, no separate music department existed. The sheet music which did come sporadically into the Museum was regarded as a problem: it was hard to catalogue by the rules appropriate to books (this remains true today), difficult to store (this also remains true), and, as music was not yet regarded as a proper subject for academic study, not particularly valued.

From the 1820s onwards the study of music grew in importance, and Museum library users started to complain about the lack of access to music in the collection. In February 1838, a piece in the journal Musical World expressed their frustration:

“Treasures there are: but the individual in search of them is in the situation of Tantalus, hearing the gurgling, ever-living springs, but doomed never to slake his thirst. Your attendant affirms that there are piles, folios, sheets innumerable of music: but they are admitted to the bewildered enquirer to be in the most admired confusion.” (Quoted in Alec Hyatt King, A wealth of music (1979), p. 29).

At the behest of Anthony Panizzi, Keeper of Printed Books, a report on the collections of music was prepared for the Trustees in 1841 by the Principal Librarian, Henry Ellis. As a result of this, it was decided to create a separate catalogue of music, both printed and manuscript. Panizzi submitted plans for the work, including eight rules to be followed by the temporary cataloguer (a fascinating smaller relative of his famous 91 rules published in the same year, and of great importance for the future development of music cataloguing). The successful candidate for this job was Thomas Oliphant, who remained in charge of the printed music collections thereafter until 1850, despite an unfriendly working relationship with Panizzi, and despite initial disapproval of his appointment from some contemporaries; the Musical World describing him as an “amateur”, and a writer in The Musical Examiner referring to him as “Mr Elephant”!

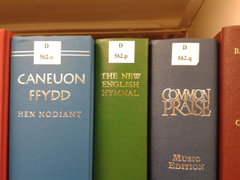

The music was physically separated from the rest of the collection, and work began on cataloguing. Oliphant separated the collection into two divisions, vocal music and instrumental music. To vocal music he assigned shelfmarks beginning with upper-case letters, and to instrumental music, shelfmarks beginning with lower-case letters. The letter indicated the height of a volume, with “A” being the smallest and “I” the tallest.

There were up to five components to a shelfmark; a letter, a number, a letter, a number, and often also a bracketed number. For example, H.5.g.3.(4.) indicated a vocal music publication, in the “H” height sequence, in the fifth press (cupboard) of that sequence, on shelf “g” of that press, in the third volume on that shelf, and comprising the fourth bound item in that volume .

This system has outlived its original cases and cupboards and in its essentials (vocal/instrumental division, height, sequential allocation of letter/number, and tract number or bound item number) is still in use today. It is accommodated in our library management system which has been “tweaked” to be case-sensitive where music shelfmarks are concerned. It has lasted due to the infinite number of possibilities for adding to Oliphant’s sequences, and has also enabled the Library to maximise space by placing items of a similar size together.

By 1850, Oliphant had single-handedly prepared catalogues of both the manuscript and printed music. The printed music catalogue alone contained 27 volumes. During his time at the Museum, Oliphant must have personally catalogued 24,000 titles! Cataloguing rules and library systems have changed vastly since then, but today’s library and catalogue users are indebted to the ingenuity and energy of these early British Library staff members.

Caroline Shaw, Music Processing and Cataloguing Team Manager 31 May 2017

Based on a presentation by James Clements, 2004, with information from: Alec Hyatt King, Printed music in the British Museum (London, 1979). YA.1997.a.10519

Share Tweet EmailCatégorie: Collections de bibliothèques